“I think writing systems must flow with their languages, like rivers,” says Juan Casco (@juancascofonts), the Ecuadorian type designer, graphic designer and researcher behind the creation of the Silabario Amazonico (@silabarioamazonico) writing system. Created to support and uplift the communication of Indigenous Amazonian languages, Silabario Amazonico encourages designers to carve out new approaches to type design that centre the whole, defined features of the languages they convey, as opposed to the infrastructure and mediation of the Latin alphabet.

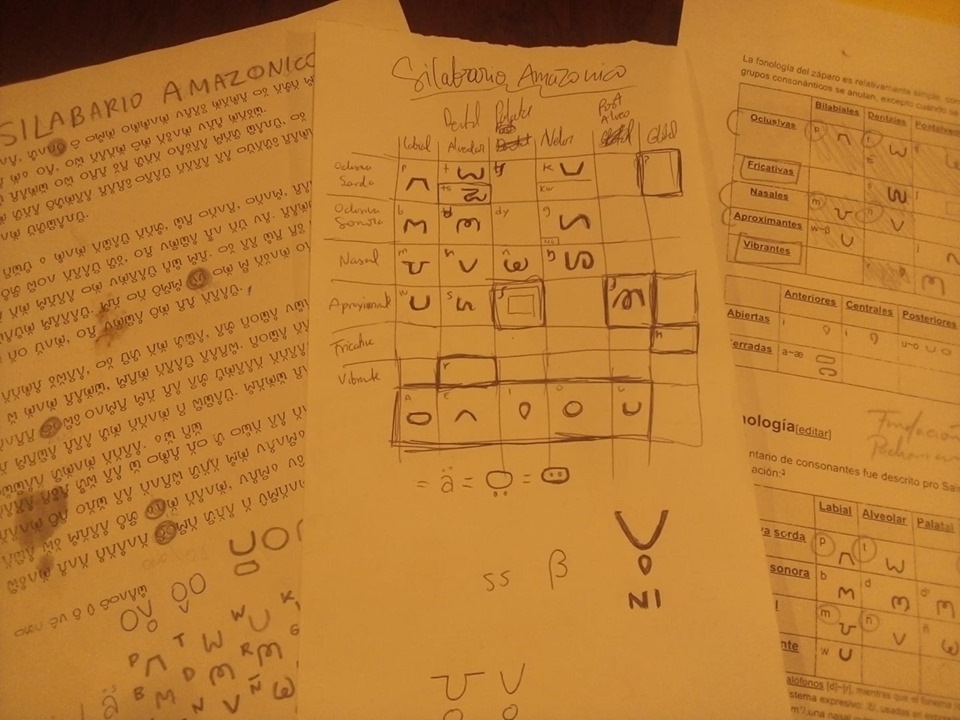

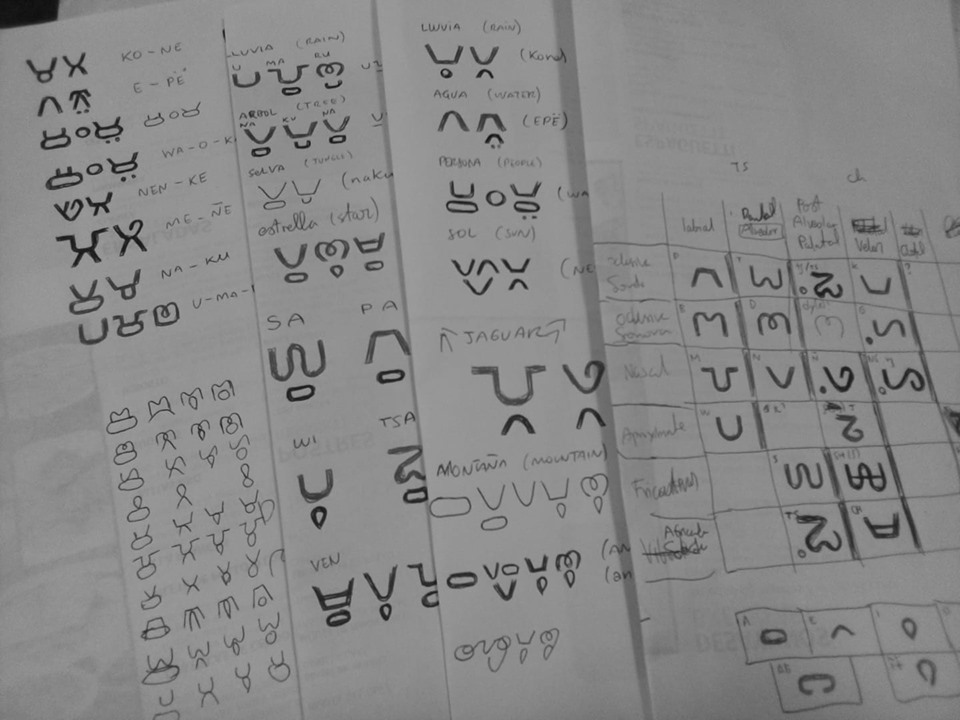

“Between 2012 and 2013,” Juan continues, “I started working closely with texts and press releases written in Amazonian languages such as Kichwa, Shuar, Achuar, Siekopai, and Wao Tededo. In time, I made a historical compendium of the antecedents of pre-Columbian writing systems, and I have made experiments with modular typography – digitising traces, shapes and characters.” Compiling research which would later lead to the development of Silabario Amazonico, Juan began a journey which would see him working with professionals in linguistics, anthropology and programming, “to create tools and methodologies,” he says, “for the dissemination and preservation of languages.”

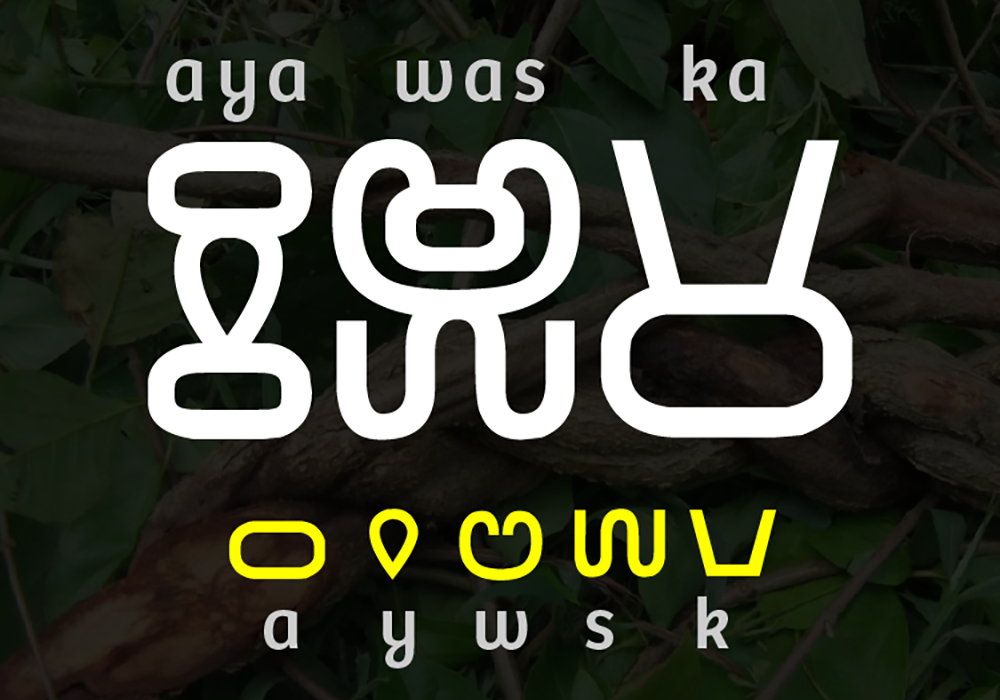

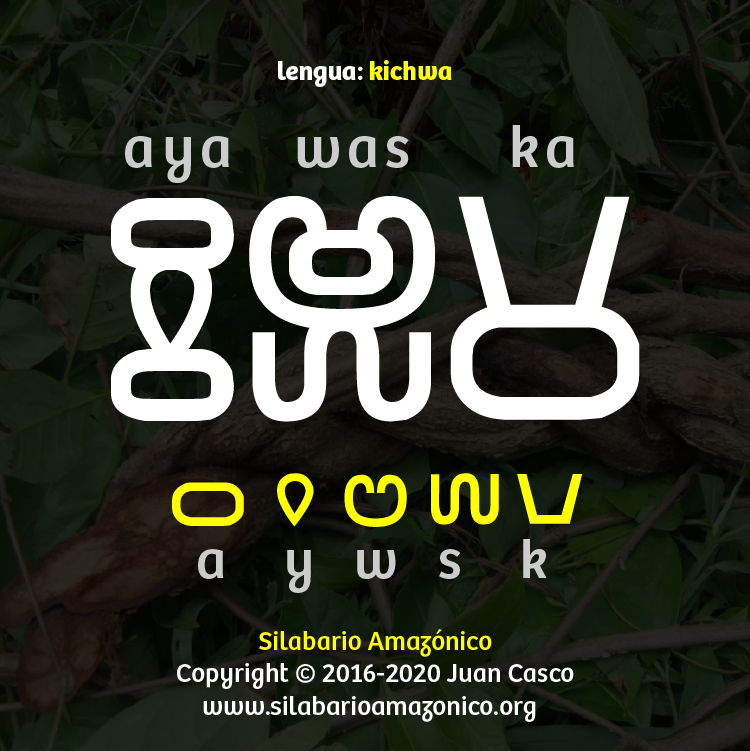

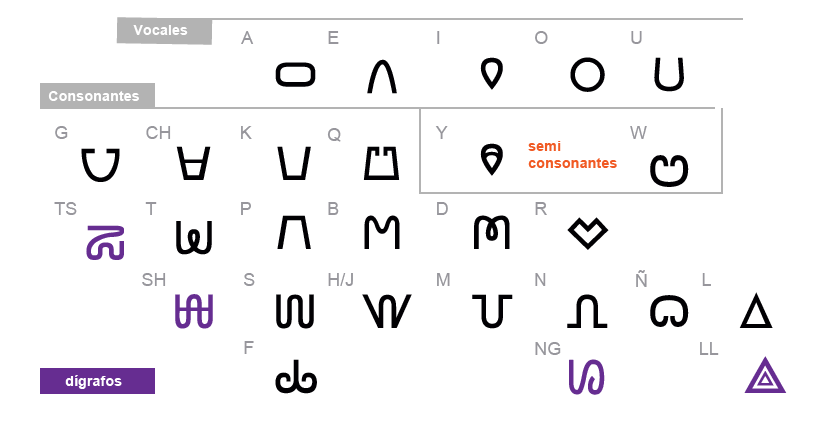

“Also known as SilAm,” Juan elaborates, “Silabario Amazonico is a writing system written as an alpha-syllabary or abugida [a segmental writing system that consists of symbols for consonants and vowels, such as Devanagari] for Indigenous languages and tongues, especially for Amazonian and Andean peoples.” Born and raised in Puyo, a city in the Pastaza Province in Ecuador – which is home to seven Indigenous nations – Juan says he grew up fascinated by “languages, history, geography, and the human spirit,” and that after developing a career in type design, he “began to conceptualise how typography could help communicate the Amazonian Indigenous languages.”

Decolonising Languages

Both in Ecuador and across the world, many Indigenous languages have have developed as agraphs (stemming from spoken traditions), and so do not have writing systems of their own. This means that nowadays, many Indigenous languages are written with Latin characters. “Indigenous and Aboriginal people have suffered strong processes of colonisation,” Juan says. “Over time, I understood that the problem itself is not the [use of] colonial written systems (commonly Latin alphabet), but the colonial consequences that the colonial languages had on the way of writing, synthesising and assimilating the original tongues for their native speakers, as well as the social and political impact of colonisation. For example, here in Ecuador educational problems are consequences of an unequal distribution of the profits from oil exploitation in the Amazon, which for the most part has only impoverished Indigenous communities.

“I realised that without a writing system,” Juan continues, “a language is more likely to be in danger of extinction – that is the reason they are still developing writing systems in Africa, for example, like the successful process of Adlam (a script used to write the West African language Fula).”

Despite the strong presence of agraphs, research has shown the existence of writing systems embedded in artefacts across in pre-Columbian America; writing systems such as the Mesoamerican (Mayan) Hieroglyphics, as well as numerical and iconographic Andean systems such as the Inca Kipus and Tokapus, have been uncovered within traditions of textiles and knot-tying.

Silabario Amazonico: Research & Inspiration

Creating a script to preserve and empower Indigenous Amazonian languages required in-depth research over many years, alongside a creative approach to developing forms that would convey the spoken word. Beginning serious academic research in 2019, Juan built a team which he called the ‘Silabario Amazonico committee,’ made up of Dr. Carlos Duche, an anthropologist and archaeologist with years of experience researching pre-Columbian peoples; Dr. Olivier Meric, a sociolinguist from Universidas Estatal Amazonica based in Puyo; and the American project manager Kayla Vandevort.

In the initial stages of research, Juan tells us he focused on the Wao Tededo language of the Waodani people, before moving on to look at the Sapara language which, he notes, is in danger of extinction and has been added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. “When I analysed the Wao Tededo language, I saw the practicality that a syllabary could present for the Wao Tededo, which is an occlusive language that presents a reduced number of phonemes: 11 consonants and 4 vowels. Sapara has digraphs like ts or ng, as well as a great amount of diphthongs and triphthongs.”

What followed was a creation process built around a collection of syllables from different Indigenous languages. “Later,” Juan counties, “I added syllables in Kichwa, which is the most widely spoken indigenous language in the country, and a little of Shuar. During this journey I also learned about the Amazonian Syllabary Afaka from Ndyuka language, a creole tongue from Surinam.”

During the research and design process, Juan also also learned about the histories of syllabaries for American languages that are used to this day, such as the Cherokee syllabary and Inuktitut. “I was inspired by the work of J. R. R. Tolkien in the construction of his languages and artificial scripts, such as the Tengwar for his elvish tongues,” he adds, as well as “the structure of the Korean alpha-syllable and the abyads, such as Hebrew or Arabic consonants with their decorative vowel points.”

Silabario Amazonico: Features & Design

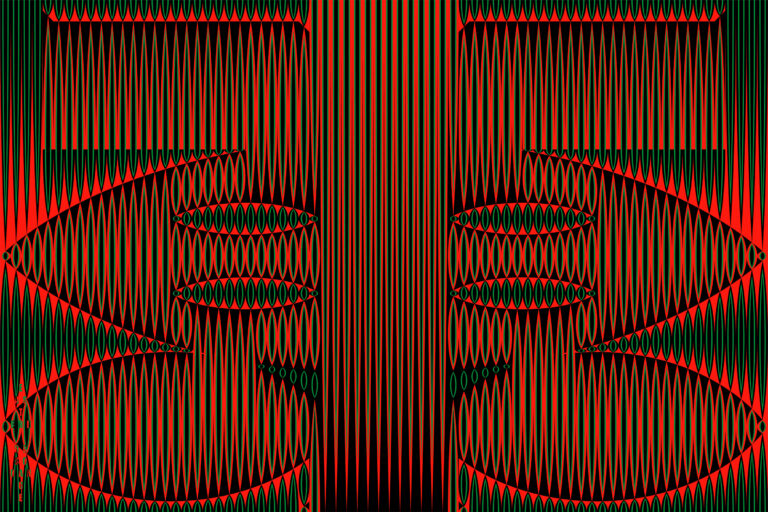

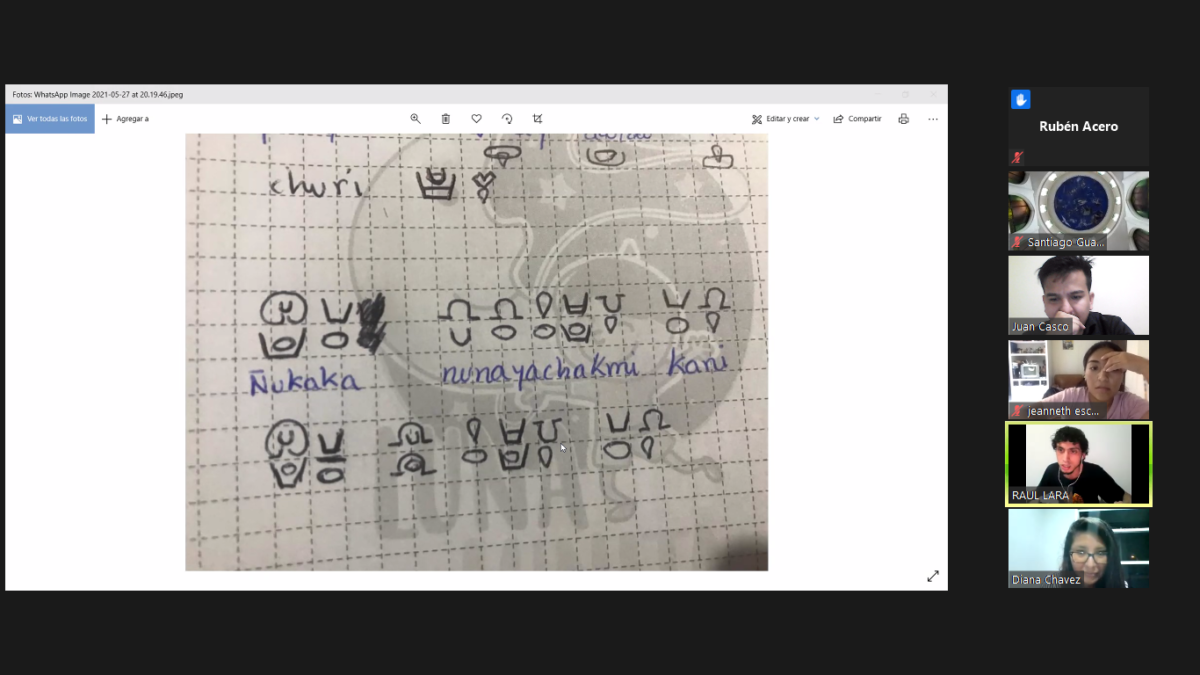

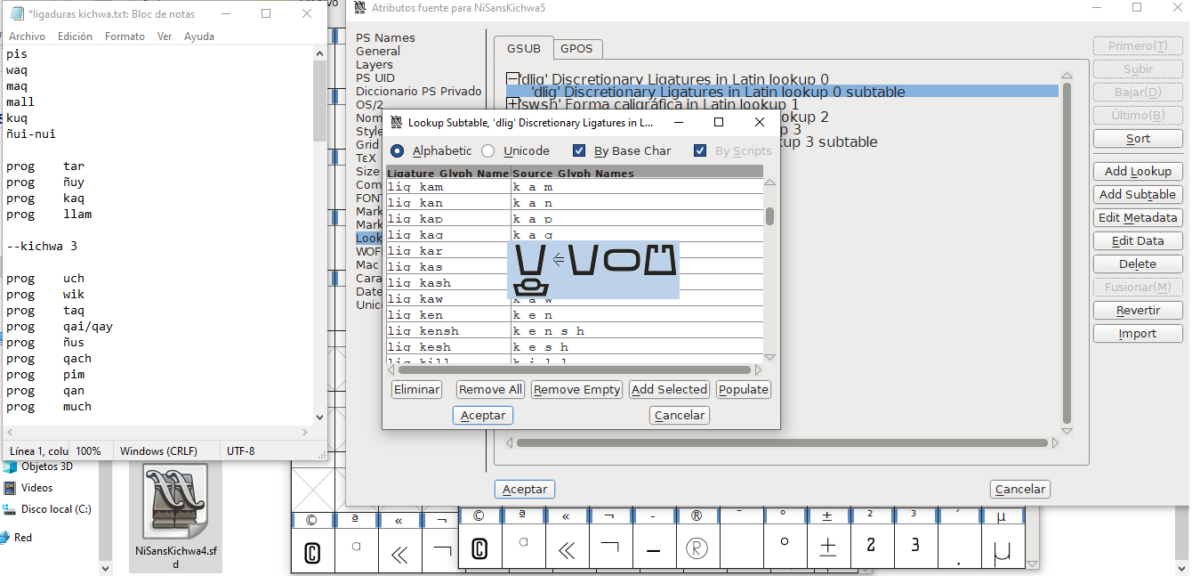

“As a type designer,” says Juan, “I knew about OpenType, so for the last two years I have been programming a font with OpenType features: contextual, discretionary, and decorative, in a very similar way to abugidas (alpha-syllabaries) like Hindi. Silabario Amazonico presents a holistic principle of construction with bilateral symmetry, glyphs of mostly a single stroke, and syllables that visually correspond to the identity of the peoples, with references to facial painting, ceramics, and even similarities to pre-Columbian petroglyphs.”

Lastly, Juan notes that such projects should not present any obligation to Indigenous people, but be seen as “decolonisation tools” – empowering Indigenous narratives through a process of “rethinking, from an anthropological, linguistic, social and educational perspective, that peoples have the right to build, evaluate and implement the form of writing that best suits their collective interest preservation and identity.”

For more on Silabario Amazonico, you can view Juan’s talk for TYPOGRAPHICS International Design Conference 2021, and stay connected on socials. Thank you, Juan.