Creative career paths tend to be non-linear. And the fact is when it comes to being a type designer, you’re often looking at merging business skills, creativity and a highly specialised skillset to make a living from the craft – essentially, there’s a lot of ways to go wrong. But while many of us know the feeling of rejection or a harsh critique pretty well, it still carries some stigma; it’s icky, and it can be as difficult to look in the face as it is tempting to erase.

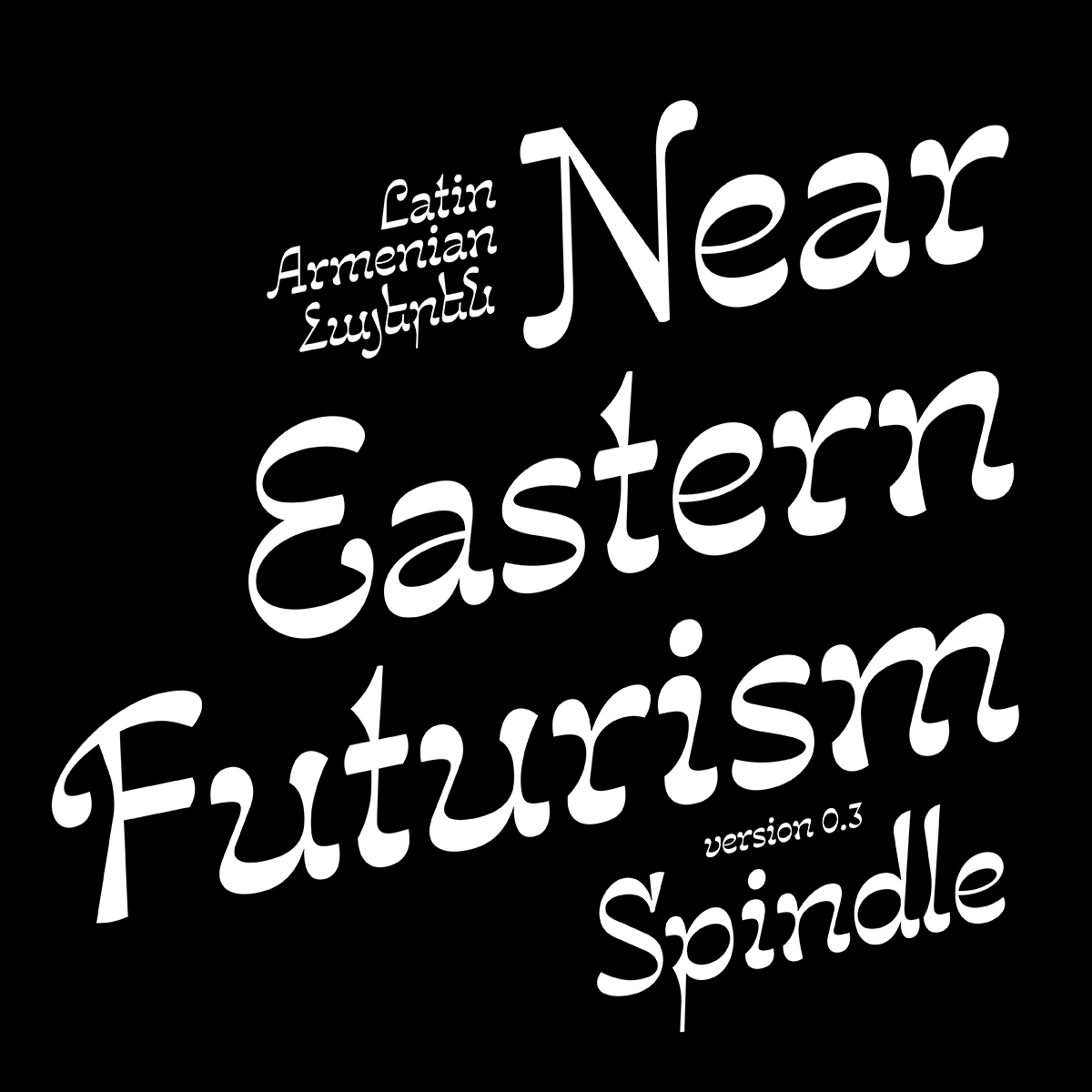

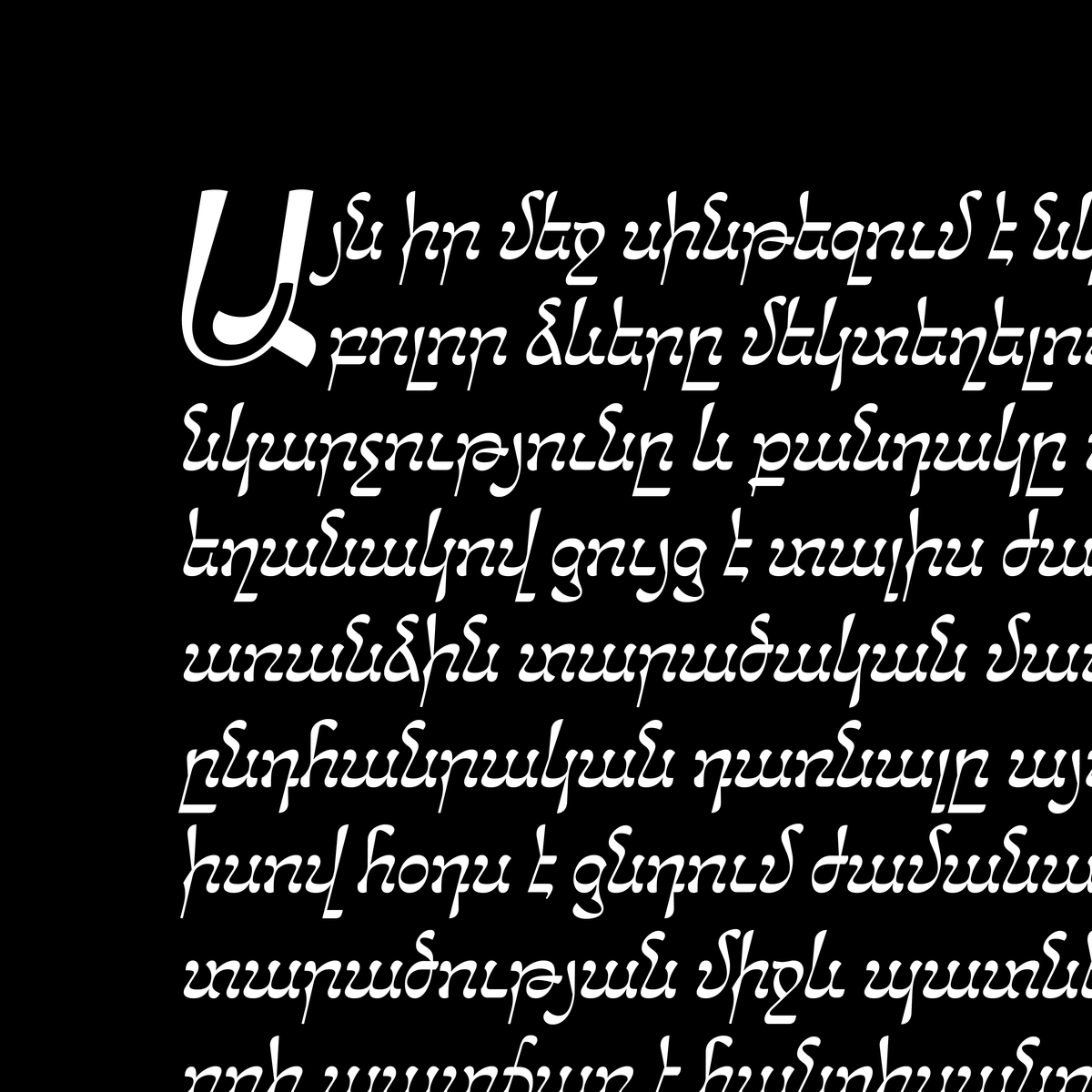

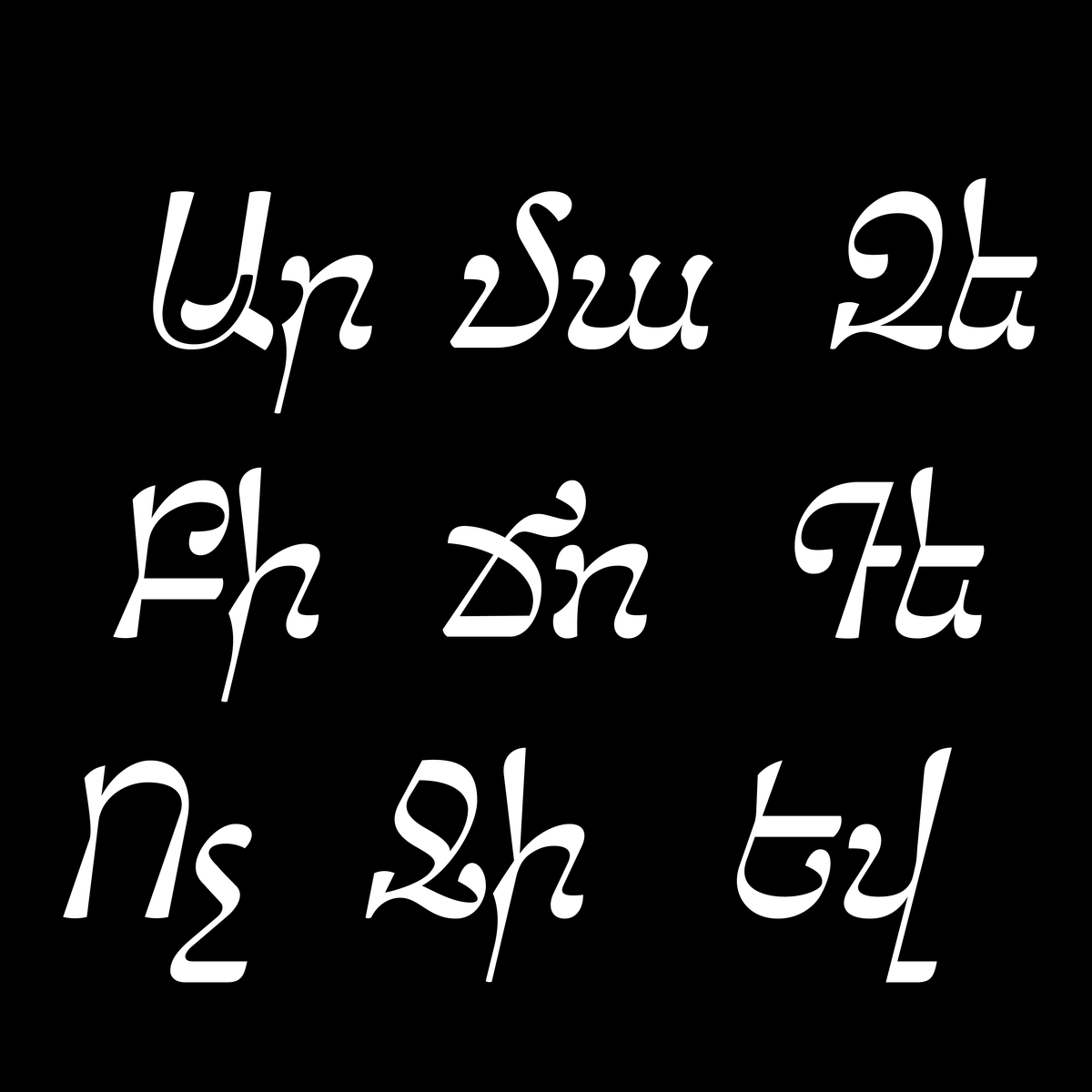

Having spoken on the subject of setbacks and rejection at Fuckup Nights Armenia (@fuckupnightsarmenia) in Yerevan during Summer 2019 (a global movement and event series that shares stories of professional failure), Gor Jihanian (@gor.jious) has a lot to say on this topic. Now a prolific type designer, he believes it’s possible to treat rejection as something generative, and is committed to highlighting the importance of detaching yourself from the pain and self-doubt that can come with negative feedback. Having taken a winding path to type design himself – starting out in Architecture before finding his way to letters – Gor speaks from a place of authenticity and experience as he shares with us his tips for transforming the experience of rejection in your career.

Firstly, can you pinpoint any particular moment of rejection or criticism in your career that had a strong impact?

Just after finishing an intensive year-long master’s program at the University of Reading, our MATD collective decided to celebrate by attending the annual ATypI conference. On the momentous Variable Font Day, I ran into the head organiser of a type competition to which I had recently submitted my typeface to. The conversation turned to criticism as he informed me of the results and began dismissing the design decisions that I had dedicated so much time and thought to researching and developing. At that moment, it was distressing to not receive constructive feedback or have a dialogue with a person who has been working in the same niche field that I was getting ready to enter. Along with that came thoughts of self-doubt, disappointment, and regret. Thankfully, with the support from my classmates and professors, that moment became a turning point – reaffirming to myself the reason I got into typeface design and realising that this career path will not be linear.

So do you think rejection is inherent in a creative career, and ultimately, is it an important part of developing creatively?

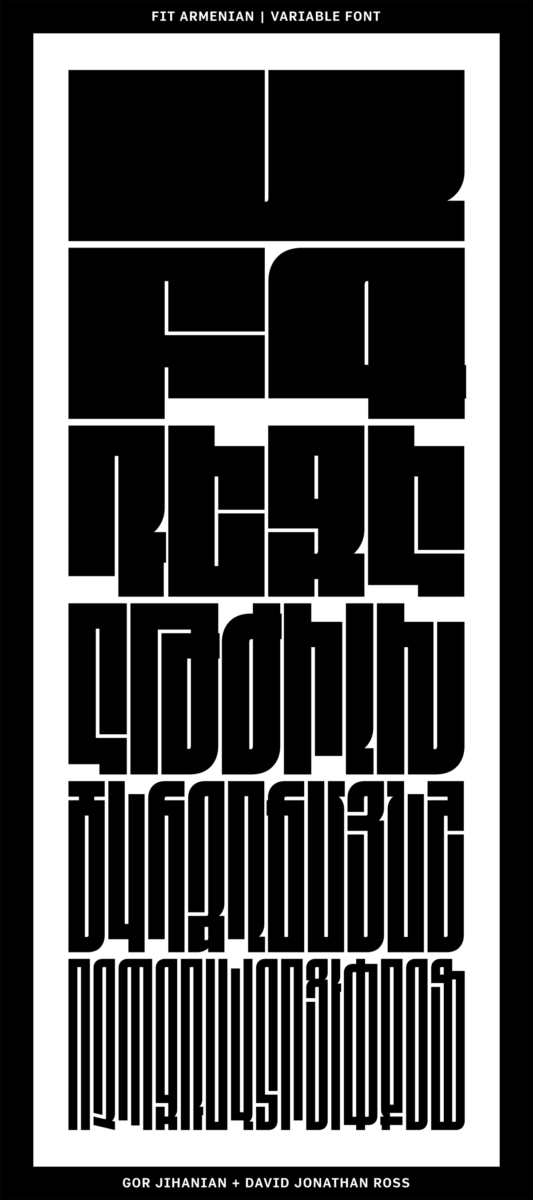

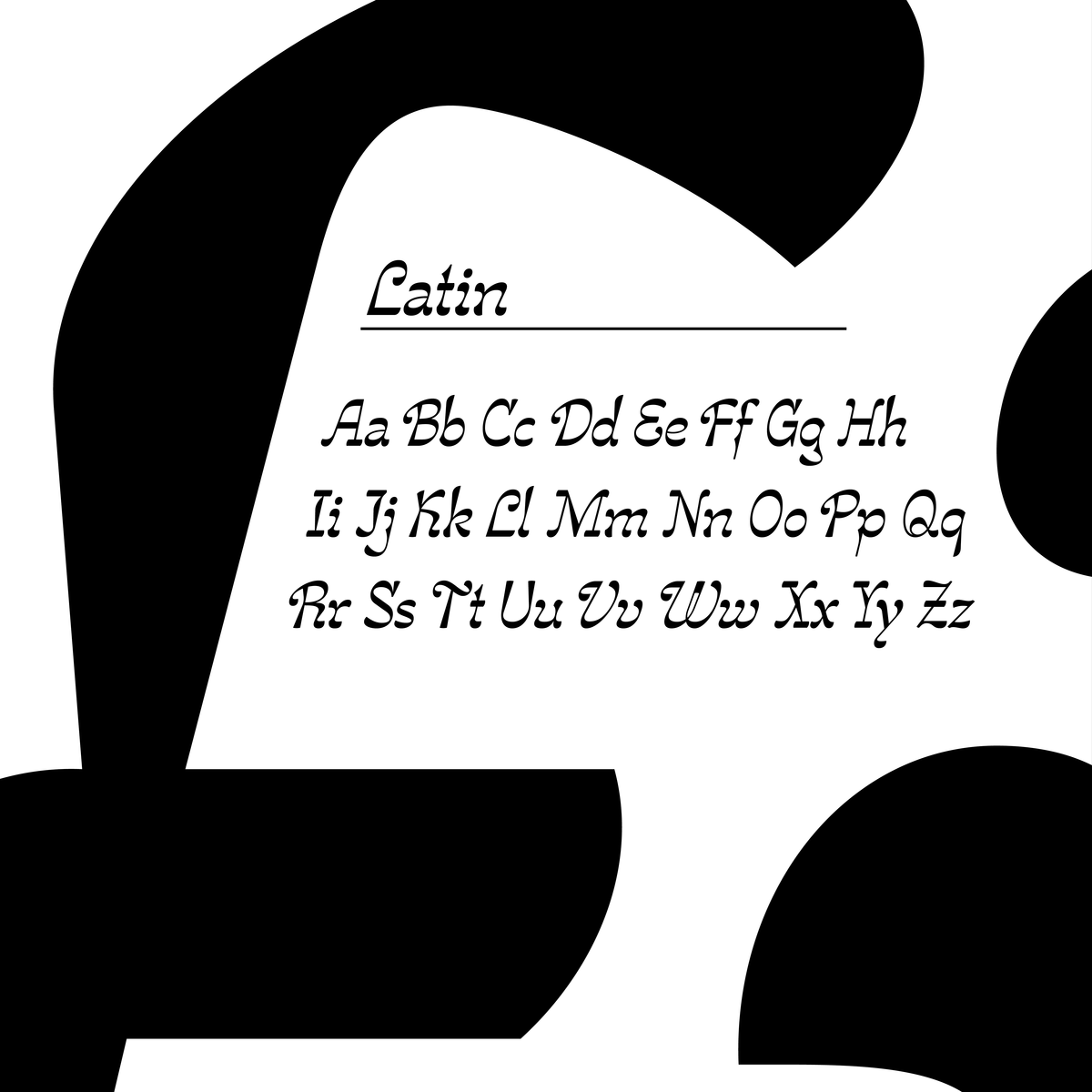

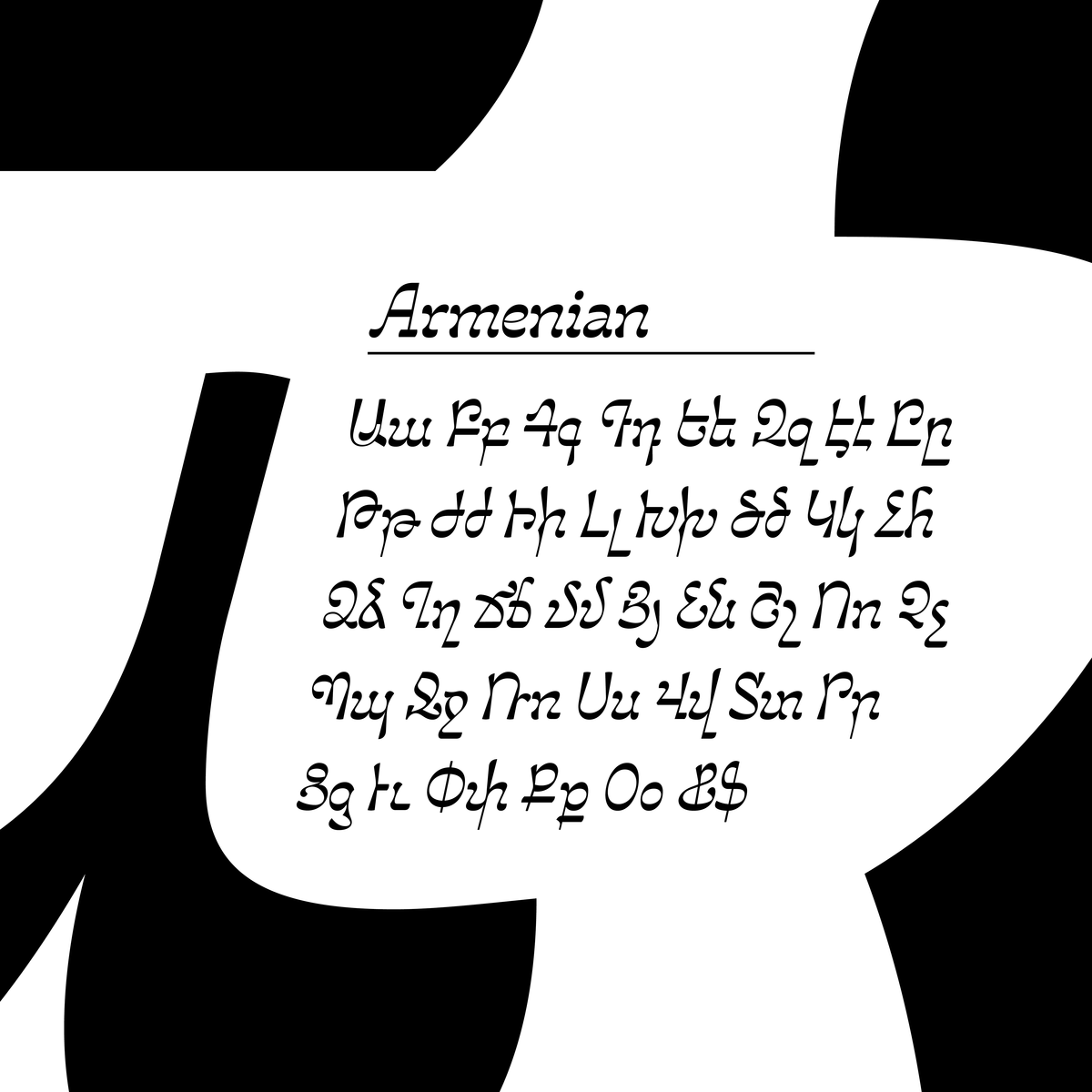

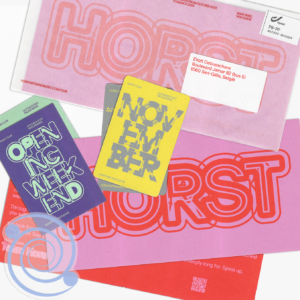

From the unemployed period after graduating to progressing professionally, I am convinced that rejection is inherent in any creative field, and with it comes an opportunity for growth. In the stressful periods between applying for jobs and waiting for responses, I would focus my energy on tangential interests by splitting time between researching manuscripts, learning code, and exploring technology. In hindsight, this initiated an important series of chain reactions: the first set the foundation of the design for Spindle, which later released on Future Fonts; the second allowed me to build my personal website from scratch, which also made it possible to build a self-initiated mini-site for Fit Armenian; and the third led to presenting at Typographics TypeLab experiments in interacting with variable fonts using physical controllers, which subsequently led to making new connections and the first major project.

Has your mind changed in the way it processes criticism or rejection since the beginning of your career to now?

Originally, my design education started in architecture – BA in Environment Design from University of Colorado at Boulder – which is notorious for its brutal(ist) jury panel where, after a series of all-nighters, tired and stressed students are required to present models and drawings while facing public critique in front of a room full of professionals and peers. After the first-year gauntlet, I was fortunate enough to have professors who disagreed with the usefulness of the competitive jury panel. Those studio classes, no less demanding, allowed for focusing on the processes of the project while promoting discussion and collaboration among classmates.

In these formative years, there was one professor in particular who shaped the way I think about design. In our studio critiques, he was adamant in the way projects are presented and discussed, continually stressing the detachment of personal emotions and ego, and instead focusing on what the project is striving to accomplish and how the series of design decisions work to achieve that goal. Of course, it is difficult especially when so much time, energy and thought goes into something, but in this way, criticism is decoupled from self-worth. After shifting paths and entering into the typeface design program, it was a welcome and familiar feeling that this approach to critique is typically among type designers. Often when I face criticism or am in a position to offer feedback, I think about these experiences.

Lastly, would your top 3 tips be to change the way you handle rejection for the better of your career?

Detach: rejection is not tied to self-worth – you are not a job or a project.

Reflect: rejection is not a setback – it is an opportunity to reassert goals and values.

Vent: rejection is universal – talk openly with friends, family, and colleagues.

Thank you, Gor!