For multi-award winning Designer Taurai Valerie Mtake, investigating the potential of design in contemporary African visual culture has been an area of interest for some time. In an ongoing project surrounding the revival of Nguni Symbol Writing, she examines Indigenous knowledge embedded within writing systems, aiming to reveal how this knowledge might be authentically and thoughtfully brought into South African contemporary visual practice, and passed on to following generations.

In the 21st century, Taurai says, traditional cultural practices often become part of “a staged authenticity” – that is, one in which “the history of meaning in the objects and designs is often lost, sometimes even to the producers themselves.” She continues, “it is in this way that important indigenous systems have been transfigured in contemporary society merely as elements of decorative art, or a curio for mass consumption…For me, there is potential in design to halt this waste and abandon of our most valuable cultural resources.”

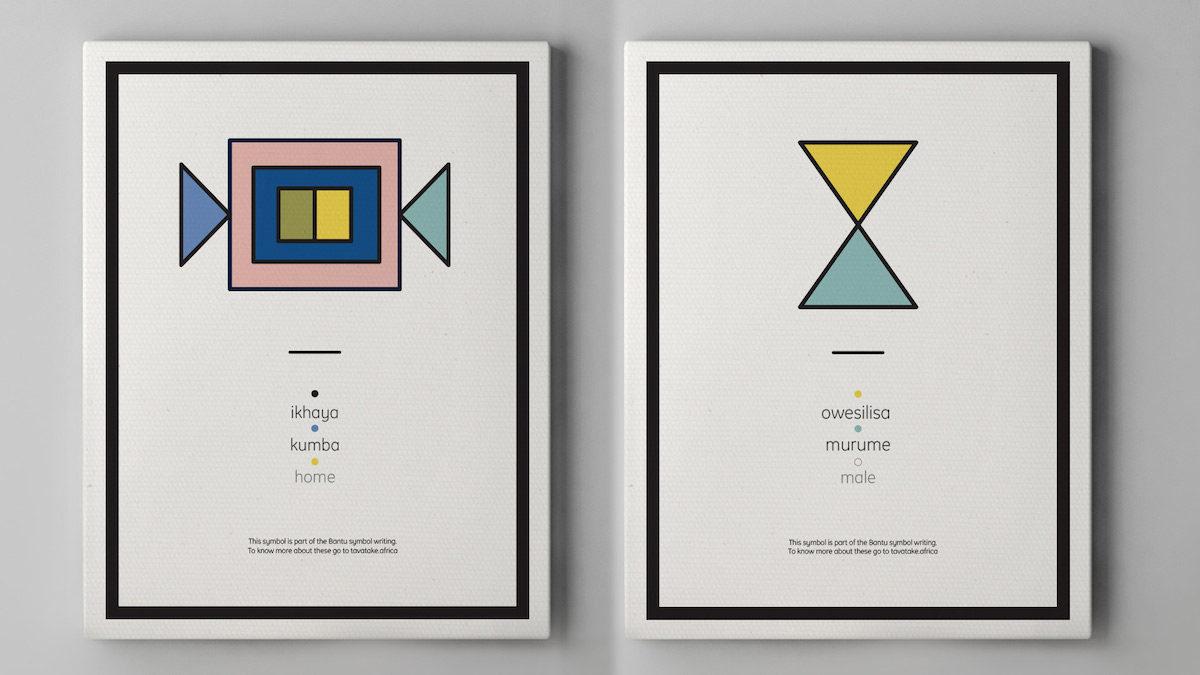

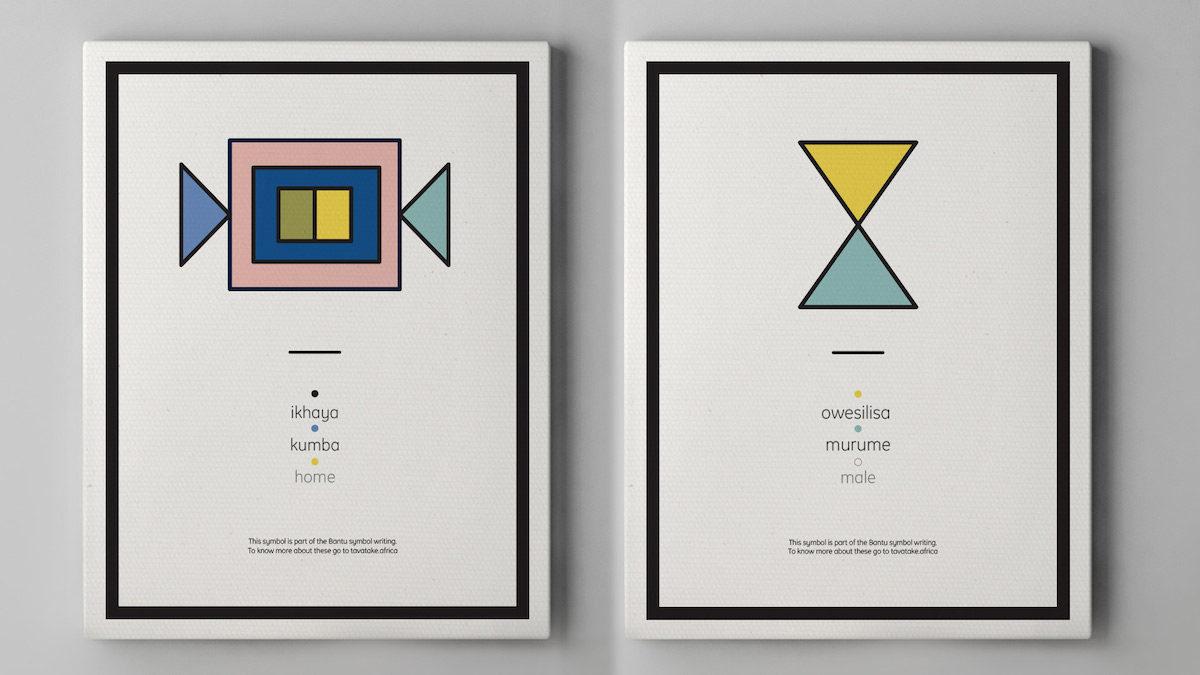

Using the Afrikaans spelling ‘Afrika’ throughout her projects, Taurai’s language and practice draws into focus the value of the continent’s Indigenous knowledge, whilst creating distance from the flattening lens of colonialism. “Symbols are a means to convey messages, emotions, needs, and desires to each other,” she writes, “and writing is a technology that facilitates these transmissions. It is one part of a broader spectrum of visual communication in contemporary society; both writing and pictures are what we call part of visual communication, but there is more to it than that…The most powerful, meaningful, and culturally important messages are those that combine words and pictures. And sometimes, they are one and the same.”

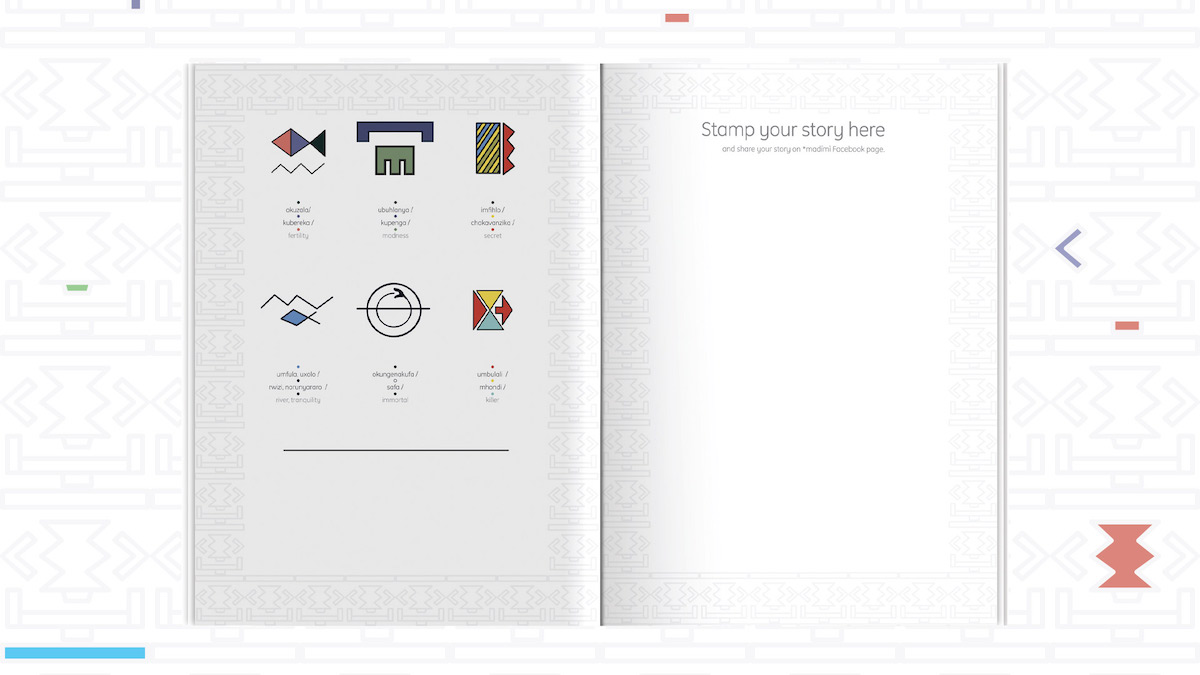

Applying her expertise in graphic design to the production of edutainment materials – which is the main objective of Taurai’s co-founded Nhaka Creative Agency, focussed on Afrikan history and cultural heritage – Taurai situates her messages within a book and board game entitled *madímì. She splits the project’s design into three key areas – Play, Learn and Tell a Story – creating a way to harness, celebrate and pass on the Indigenous knowledge embedded in Nguni Symbol Writing, complete with its own visual identity system and custom typeface tailored to fleshing out its message.

Play

“The visual identity for the *madímì project integrated the original Nguni symbol meaning conversation, because graphically bringing back the beautiful, colourful symbols into contemporary visual society could be seen as a civilisation with our ancestors – and perhaps with future generations,” Taurai explains.

“*madímì is a reconstructed word in Proto-KiNtu. Proto-KiNtu is the reconstructed ancestor of all KiNtu languages. It consists of two parts: ma- (a plural noun prefix) and -dimi (a noun root meaning “language” or “tongue”). The * indicates that the word is reconstructed. The letters are written in the International Phonetic Alphabet, which tells how to pronounce the word, not how it is spelled. The vowel ‘í’ has a different sound from the vowel ‘i’; the little marks on top of the vowels indicate the tone. KiNtu languages are tonal languages – meaning whether you pronounce the vowel with a high or low tone, it can change the meaning.”

Learn

“This book endeavours to join in the de-colonial assertion that Southern Afrikan people have, indeed, always had their indigenous writing systems,” she continues. “However, through the process of colonisation in line with the Western construct of ‘civilisation,’ projects enforcing the Roman alphabet as a literary standard discouraged the wider use of indigenous writing cultures and effectively disinherited many Afrikans of this heritage. There have been many movements around the continent to reinstate indigenous written heritage, however.”

“These pages serve as a gesture in that spirit, recataloging the indigenous symbology described in the classic works of Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa in the context of both ancient and modern indigenous symbolic cultures of the region of Southern Afrika. Moreover, this book offers some ideas for how this expressive tradition can once again become part of the everyday visual culture of Afrikans like ourselves, as game objects and storytelling tools. This is so that young Afrikans may access the creative tools of their ancestors and feel their place in a great cultural history going back generations, in order to build a new Afrikan future that is not yet imagined.”

Tell a Story

“The children tell a story through stamping in a book or poster that can be shared with friends, or the parents take a photo of their child’s story. This encourages parents to engage in this awareness project – thereby learning the symbols – and further encourages the broader community to participate. The aim of this project is to promote awareness of indigenous visual culture, bringing our origins to the fore, and making the symbolic vocabulary of our ancestors available to today’s young generations as a creative tool to develop their skills and express themselves as Afrikans while understanding their place in a great cultural history, so they feel part of something exciting that goes back generations.”

Thank you, Taurai.